Innocent?

GUILTY UNTIL PROVEN

Investigating Flawed Forensic Science and Miscarriages of Justice

Justice Denied: The Long Road to Exonerating David Milgaard

Guy Paul Morin

Kyle Unger

Thomas Sophonow

Jessica Kazerani March, 30, 2023

Additional Cases

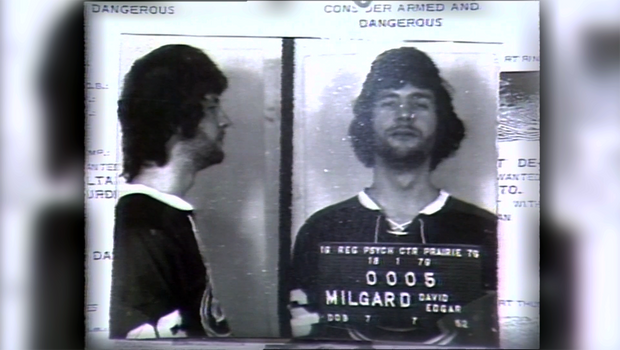

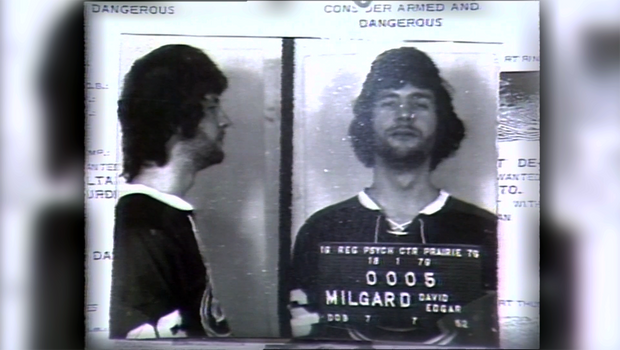

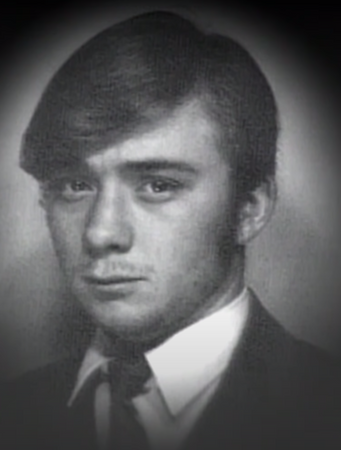

Imagine being a 16-year-old who is falsely accused and imprisoned for manslaughter. This was the unfortunate reality for David Milgaard back in 1969 when he was convicted for the sexual assault and murder of Gail Miller and sentenced to life in prison. He tirelessly fought for decades to clear his name in what’s known to be one of the most notorious cases of wrongful conviction in Canadian History - highlighting the importance of the presumption of innocence!

A Case of Being in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

A well-known case in Canadian legal history involving a miscarriage of justice is the murder of Gail Miller and the wrongful conviction of David Milgaard. On January 31, 1969, 16-year-old David Milgaard was passing through Saskatoon, Saskatchewan with friends, while on a road trip from Regina to Vancouver. On that same day, the body of 20-year-old nursing assistant, Gail Miller, was discovered in a snowbank a block and a half from where Milgaard was staying at the time. Despite having an alibi and no physical evidence linking him to the crime, Milgaard was arrested and convicted of the rape and murder of Gail Miller based on circumstantial evidence and the testimony of witnesses who later recanted their statements. The prosecution relied on the idea that Milgaard was in the vicinity of the crime scene at the time of the murder, and that his behavior was suspicious.

There were several flaws in the police investigation into Miller’s murder that led to Milgaard’s wrongful conviction, including tunnel vision, inadequate testing of forensic evidence, and reliance on coerced and unreliable eyewitness testimony. Despite this, Milgaard was sentenced to life in prison and spent 23 years behind bars before being released in 1992 and exonerated in 1997. In the 1990s, advances in DNA technology allowed for the reexamination of the DNA evidence that was used to convict Milgaard. The results showed that Milgaard could not have committed the crime and pointed to the real culprit, Larry Fisher, who was already serving time in prison for other sexual assaults and attempted murder. This evidence was presented to the courts and Milgaard was finally exonerated along with a formal apology from the Canadian government and compensation. Furthermore, the Government of Saskatchewan ordered a public inquiry into the causes of David’s wrongful conviction.

David Milgaard

There were several flaws in the police investigation into Miller’s murder that led to Milgaard’s wrongful conviction, including tunnel vision, inadequate testing of forensic evidence, and reliance on coerced and unreliable eyewitness testimony. Despite this, Milgaard was sentenced to life in prison and spent 23 years in prison before being released in 1992 and exonerated in 1997. In the 1990s, advances in DNA technology allowed for the reexamination of the DNA evidence that was used to convict Milgaard. The results showed that Milgaard could not have committed the crime and pointed to the real culprit, Larry Fisher, who was already serving time in prison for other sexual assaults and attempted murder. This evidence was presented to the courts and Milgaard was finally exonerated along with a formal apology from the Canadian government and compensation. Furthermore, the Government of Saskatchewan ordered a public inquiry into the causes of Milgaard’s wrongful conviction.

Glen Assoun

the investigation

On January 31, 1969, David Milgaard and his friends Ron Wilson and Nichol John embarked on a road trip from Regina to Vancouver. They left Regina shortly after midnight, planning to pick up another friend, Albert Cadrain, in Saskatoon. They arrived at Cadrain’s house around 9 a.m, and they all set out for Calgary later that day.

Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, Cadrain’s basement tenant, Larry Fisher, was a serial rapist who had just sexually assaulted and murdered Gail Miller that same morning as she was on her way to work. Miller was raped, stabbed to death with a paring knife, and left in a snowbank at approximately 6:45 a.m.; her body was discovered two hours later. Police quickly sought out known sex offenders in the area to question them; in fact, they investigated over 160 possible suspects without finding any helpful leads.

On March 2, 1969, Cadrain contacted Saskatoon Police, claiming that Milgaard had been behaving suspiciously and had bloodstains on his clothing on the morning of Miller’s murder. Milgaard was not a suspect nor was he known to the Saskatoon Police prior to this. Within 24 hours, police located Milgaard in Winnipeg and questioned him, and he denied any involvement in the crime. Many years later, it emerged that Cadrain was a police informant who received a $2,000 reward for providing this “evidence”. He was said to have shown signs of mental illness before the trial and three years after Milgaard’s conviction, he was also diagnosed with schizophrenia. The inquiry received evidence that Cadrain’s stated reason for contacting police was that he had hallucinations of the Virgin Mary stepping on a snake with Milgaard’s face.

Over the following weeks, the police conducted interviews with Milgaard and several of his friends and acquaintances. John and Wilson initially provided strong alibis for him and told police that Milgaard had been with them throughout the morning of the attack on Miller and that he had nothing to do with it.

Gail Miller

Albert Cadrain

Milgaard convicted

Investigators began hearing reports that Milgaard had entertained friends in a Regina hotel room by re-enacting the Miller murder. The police concluded that John and Wilson had lied in their initial statements and subjected them to further interrogations. Eventually, during a lengthy interrogation using a polygraph test, they changed their statements, claiming they also saw blood on Milgaard’s clothes, and that they had seen him with the murder weapon. John went so far as to claim that she had suddenly remembered witnessing the murder.

On May 30, 1969, Milgaard was arrested and charged with the rape and first-degree murder of Gail Miller. His trial commenced nine months later before a judge and jury. Milgaard faced a difficult trial maintaining his innocence as the prosecution used his former friends’ statements against him. Although John refused to say that she had seen Milgaard stab Miller on the stand – which, of course, she had not – the prosecutor still read her statement to the jury. If the jury believed that John had witnessed the crime in progress, then of course they would have to find Milgaard guilty.

After the Crown had presented its case, Milgaard’s lawyer elected to call no evidence, which means that he did not present any evidence or witnesses in support of Milgaard’s defence. This is a common strategy in criminal trials, especially when the defence feels that the prosecution has not presented a strong case. However, in Milgaard’s case, this decision ultimately proved to be a mistake, as the prosecution was able to convince the jury of Milgaard’s guilt without any strong opposition from the defence.

Although current DNA technology was not available at the time of the investigation, the semen recovered from Miller’s vagina during her autopsy was not subjected to any laboratory tests and the semen stains on her white nursing uniform were also overlooked by the crime laboratory and not submitted to forensic analysis. Furthermore, there were two drops of yellowish fluid found four days after the murder at the spot police found Miller’s body. Saskatoon Police Chief Joseph Penkala, the chief investigating officer in the Milgaard case testified to seeing these drops. One of the drops was later identified as semen and used as evidence to link Milgaard to the crime simply because he had type A blood, and the seminal fluid was determined to contain type A blood antigens, which actually happens to be present in about 40% of the population.

On January 31, 1970 - exactly one year after Miller’s death - the jury found Milgaard guilty and he was sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for at least 10 years. He maintained his innocence and attempted to convince the higher courts of his innocence. However, his appeal to the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal was dismissed on January 5, 1971, and the Supreme Court of Canada refused him leave to appeal on November 15 of that year. It was not until years later that new evidence was uncovered that led to his release from prison and his eventual exoneration

Larry Fisher

Nichol John

Ron Wilson

joyce milgaard's campaign

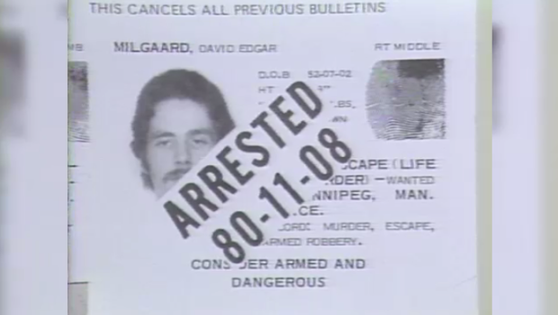

Milgaard spent 23 years in prison, enduring physical and sexual assault, which led to several suicide attempts. In 1980, he managed to escape for 77 days before being shot and recaptured by the RCMP.

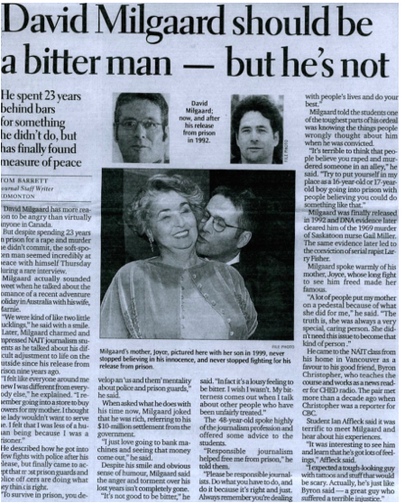

His mother, Joyce Milgaard, was relentless in her pursuit of justice for her son, launching her own investigation, sharing his story with the media, and spending all her savings in a quest to expose the truth. She supplied journalists with a stream of angles over the years to keep her son’s story alive and exert pressure on authorities. She even confronted federal justice minister Kim Campbell and threatened to camp on the lawn of the Saskatchewan legislature.

Meanwhile, the actual perpetrator, Larry Fisher, had been arrested for yet another sexual assault in September 1970, and pleaded guilty to four sexual assaults in December 1971, leading to his incarceration. He was released from prison in 1980 and quickly returned to his violent behaviour against women. On June 11, 1981, Fisher was convicted of rape and attempted murder.

Fisher’s ex-wife, Linda Fisher, went to the Saskatoon police station in August of 1980 to report her suspicions that Fisher had killed Miller. She said that she had been arguing with Fisher on the day of the murder, when a news report about the crime played on the radio. In the heat of the moment, she angrily accused him of being responsible for the murder and was taken aback by his shocked reaction. She also noticed that they were missing a paring knife from the kitchen. Although the inspector who spoke with her deemed her to be credible, police did not pursue the matter further, despite the possibility that they have imprisoned an innocent person.

Joyce Milgaard continued her own investigations, discovering in March of 1983, that Fisher had been living in Cadrain’s basement at the time of the murder. This revelation was a crucial piece of new evidence that ultimately led to the long-overdue conviction of the true culprit.

NEW EVIDENCE

On December 28, 1988, Milgaard applied to the Minister of Justice for a review of his conviction under section 690 of the Criminal Code, but his application was dismissed. He filed a second application on August 14, 1991, arguing that Fisher had committed the crime. This time, as public pressure mounted due to media reports about his wrongful conviction, the Minister of Justice referred his application to the Supreme Court of Canada. The court heard a Reference re Milgaard in 1992, which found that his continued conviction would amount to a miscarriage of justice if an opportunity was not provided for a jury to consider the fresh evidence.

The fresh evidence presented in Milgaard’s defence included a recantation by witness Ron Wilson, who had given false testimony under pressure during police interrogation. Wilson admitted to falsely incriminating Milgaard, and said that he had been experiencing withdrawal from his drug addiction after being in police custody for two days. During his polygraph session, he realized he could end the interview and return to his normal life by providing answers that aligned with what the police wanted to hear. When he was briefly placed in the same room as Nichol John, he urged her to comply with the police and implicate Milgaard. He admitted to lying about seeing blood on Milgaard’s clothes and seeing him with a paring knife, and also says he was coerced and scared that if they did not charge Milgaard they would charge him instead.

Another key piece of evidence was the confession by Fisher, in which he had admitted to committing six sexual assaults, including four in the same area of Saskatoon where Miller was killed, raising the very real possibility that she was another of his victims.

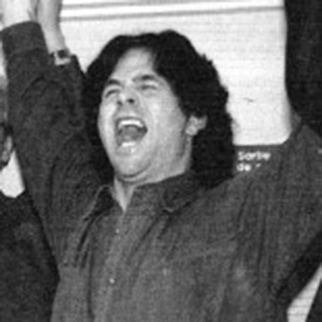

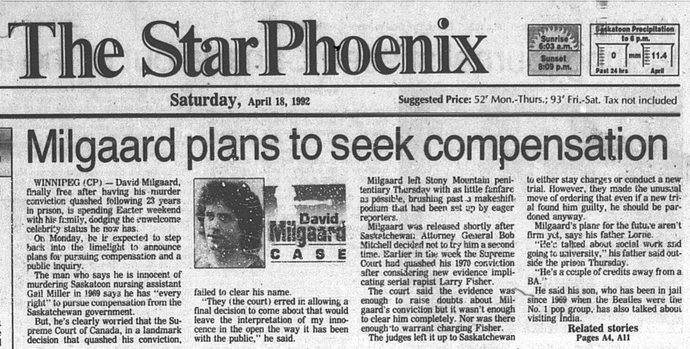

The Supreme Court heard the fresh evidence in 1992. On April 14, 1992, the Court concluded that Milgaard’s conviction should be quashed and a new trial ordered. The Crown decided not to retry him and instead entered a “stay of proceedings,'' which meant that although he was freed from prison, his name had not been cleared. After 23 years, he was finally released, but spent an additional 5 years trying to clear his name.

innocence canada investigation

Milgaard initiated a lawsuit in 1993, accusing Saskatchewan justice officials and police of wrongdoing and a subsequent cover-up. However, the legal proceedings progressed slowly, prompting Milgaard to reach out to James Lockyer, a lawyer with Innocence Canada (formerly AIDWYC), in 1996. It was known that the Crown had retained semen samples found on Miller’s clothing, and AIDWYC pressed for them to be tested for DNA in hopes of definitively clearing Milgaard’s name.

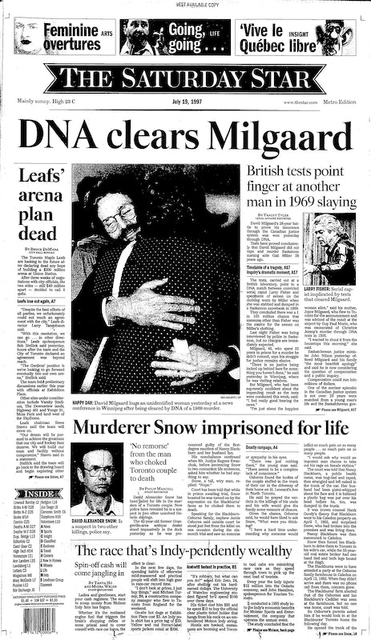

It took years of legal battles for Lockyer to obtain the samples and arrange for them to be tested at a lab in the United Kingdom. They were able to enlist forensic scientific techniques that had not been available at earlier stages of the process. On July 18, 1997, DNA testing results confirmed that the semen found in Miller’s clothing could not belong to Milgaard. Instead, the results conclusively implicated Fisher as the perpetrator.

Fisher was arrested on July 25, 1997, and was subsequently found guilty of Gail Miller’s murder on November 22, 1999, owing to the DNA evidence linking him to the victim. He was sentenced to life in prison and died in 2015 at the age of 65.

On December 28, 1988, Milgaard applied to the Minister of Justice for a review of his conviction under section 690 of the Criminal Code, but his application was dismissed He filed a second application on August 14, 1991, arguing that Fisher had committed the crime. This time, as public pressure mounted due to media reports about his wrongful conviction, the Minister of Justice referred his application to the Supreme Court of Canada. The court heard a Reference re Milgaard in 1992, which found that his continued conviction would amount to a miscarriage of justice if an opportunity was not provided for a jury to consider the fresh evidence.

The fresh evidence presented in Milgaard’s defence included a recantation by witness Ron Wilson, who had given false testimony under pressure during police interrogation. Wilson admitted to falsely incriminating MIlgaard, and said that he had been experiencing withdrawal from his drug addiction after being in police custody for two days. During his polygraph session, he realized he could end the interview and return to his normal life by providing answers that aligned with what the police wanted to hear. When he was briefly placed in the same room as Nichol John, he urged her to comply with the police and implicate Milgaard. He admitted to lying about seeing blood on Milgaard’s clothes and seeing him with a paring knife, and also says he was coerced and scared that if they did not charge Milgaard they would charge him instead.

Another key piece of evidence was the confession by Fisher, in which he had admitted to committing six sexual assaults, including four in the same area of Saskatoon where Miller was killed, raising the very real possibility that she was another of his victims.

The Supreme Court heard the fresh evidence in 1992. On April 14, 1992, the Court concluded that Milgaard’s conviction should be quashed and a new trial ordered. The Crown decided not to retry him and instead entered a “stay of proceedings,'' which meant that although he was freed from prison, his name had not been cleared. After 23 years, he was finally released, but spent an additional 5 years trying to clear his name.

Milgaard initiated a lawsuit in 1993, accusing Saskatchewan justice officials and police of wrongdoing and a subsequent cover-up. However, the legal proceedings progressed slowly, prompting Milgaard to reach out to James Lockyer, a lawyer with Innocence Canada (formerly AIDWYC), in 1996. It was known that the Crown had retained semen samples found on Miller’s clothing, and AIDWYC pressed for them to be tested for DNA in hopes of definitively clearing Milgaard’s name.

It took years of legal battles for Lockyer to obtain the samples and arrange for them to be tested at a lab in the United Kingdom. They were able to enlist forensic scientific techniques that had not been available at earlier stages of the process. On July 18, 1997, DNA testing results confirmed that the semen found in Miller’s clothing could not belong to Milgaard. Instead, the results conclusively implicated Fisher as the perpetrator.

Fisher was arrested on July 25, 1997, and was subsequently found guilty of Gail Miller’s murder on November 22, 1999, owing to the DNA evidence linking him to the victim. He was sentenced to life in prison and died in 2015 at the age of 65.

compensation and inquiry

The Milgaard case remained a topic of public and media outrage. This pressure forced the Saskatchewan government to appoint Alan Gold, retired Quebec Superior Court Justice, to negotiate a compensation package for Milgaard. His recommendation of a $10-million settlement was accepted by the government in May 1999.

In 2004, in response to further demands, the Government of Saskatchewan ordered a public inquiry into the causes of Milgaard’s wrongful conviction. The inquiry was conducted by Justice Edward P. MacCallum of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench. In 2008, MacCallum released a series of recommendations and findings, many of which focused on the handling and disclosure of evidence.

One significant finding was that a Saskatoon police polygrapher, Roberts, had exerted unacceptable pressure on John and Wilson during a lie detector test, causing them to alter their statements and ultimately led to Milgaard’s wrongful conviction. The combination of pressure from the police and encouragement from her friend Wilson seemed to have an even more powerful effect on John, who described not only recalling but having flashbacks to a crime scene that was not real. Roberts interrogated her in the belief that Milgaard was the killer and showed her the victim’s bloody garment, asking her how she would feel if it had been her sister. In his attempt to elicit what he believed to be the real story from these two young people, the polygrapher actually induced them to fabricate a narrative that would put Milgaard in jail while ensuring that the real criminal would not be brought to justice for over two decades. The Saskatoon Police Service formally apologized to Milgaard in December 2006.

Commissioner MacCallum criticized the police's failure to investigate Linda Fisher’s report on her suspicions that Fisher had killed Miller. Although her report was received, filed, and referred, it was not thoroughly evaluated or further investigated. In order to prevent future mistakes of this kind, Commissioner MacCallum recommended that “mandatory channels of reference should be put in place” for following up this type of complaint. In other words, police should be required to find out whether there is truth to allegations like this to prevent subjective character judgments from hindering an investigation

Finally, it is important to note that Milgaard’s name was only cleared once DNA testing had proved that Fisher was the real murderer. This technology was not available when Milgaard first went to trial. As scientific knowledge and forensic techniques continue to advance, more people will continue to be exonerated.

A Recommendation for prevention

To prevent a situation like the wrongful conviction of David Milgaard from happening again, I would recommend that police departments implement specific protocols and training for handling young witnesses and accused individuals. The wrongful conviction of Milgaard was the result of a flawed investigation, including false testimony from young witnesses who were subject to pressure from police officers. In order to avoid eliciting false testimony, police must remember the vulnerability of young individuals, and that they must be handled with great care. This should include providing specialized training to officers on how to handle interviews with young individuals, and establishing clear guidelines on the appropriate use of interviewing techniques in order to elicit accurate and unbiased testimony.

Specifically, ensuring that an extra person is present when taking a statement from a young individual, preferably someone who is trained in child development and/or forensic interviewing. Additionally, officers should ensure that every statement taken from a young individual in a major case, whether as a witness or a suspect, is both audio and video recorded. Young individuals are particularly vulnerable to being coerced or misled during interviews with law enforcement. They may not always fully understand the situation or the consequences of their statements. Additionally, they may be more susceptible to pressure from authority figures which could lead to false confessions or inaccurate testimony.

By implementing protocols and training that take into account the vulnerabilities of young individuals, police departments can help ensure that justice is served in a fair and impartial manner. The requirement for an extra person to be present during interviews and the use of video or audio recordings can prevent the manipulation of young individuals and provide an objective record of the interview, which can help to prevent false testimony or coercion from occurring in the first place.

Check out David Milgaard's channel here!

later years

In the years following his exoneration, Milgaard bravely spoke about his experiences and became an advocate for prison reform and the rights of the accused. He worked with the federal department of justice to establish a commission to investigate cases of alleged wrongful conviction, demonstrating his commitment to preventing others from suffering similar injustices.

Milgaard went on to marry and had two children, settling in Cochrane, Alberta with his family. Sadly, Joyce Milgaard died in a Winnipeg care home in 2020 at age 89 and David Milgaard died of pneumonia at a Calgary hospital on May, 15 2022 at the age of 69. Following his death, psychologist Dr. Patrick Baillie, who testified at Milgaard’s wrongful conviction inquiry, shared that, “Milgaard wanted to live life to the fullest with the time that was available to him and not carry a grudge despite the injustices he faced. His life was always defined by something he did not do and he wanted the opportunity to define his life on the basis of the things that were important to him."

sources & further readings

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Vol. 1, Chapter 3: 36-293.

- Reference re Milgaard (Can.), 1992 CanLII 96 (SCC), [1992] 1 SCR 866, <https://canlii.ca/t/1g2wg>, retrieved on 2023-02-06

- Rossmo, D. K. Dissecting a Criminal Investigation. J Police Crim Psychol. 2021; 36(1):639–651. doi:10.1007/s11896-021-09434-1.

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Public Documents: 217573, 219255.

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Public Documents: 159853, 229913, 278893-4.

- Stefanidou M, Alevisopoulos G, Spiliopoulou C. Fundamental issues in forensic semen detection. West Indian Med J. 2010;59(3):280-283.

- Innocence Canada. David Milgaard. 2023. https://www.innocencecanada.com/exonerations/david-milgaard/#ftn8. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- SaskToday.ca. Video: Hear David Milgaard's own words on his wrongful conviction. 2022. https://www.sasktoday.ca/north/local-news/video-hear-david-milgaards-own-words-on-his-wrongful-conviction-5621902. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- The StarPhoenix. Commission of Inquiry into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. 2005. https://injusticebusters.org/05Milgaard/Milgaard6.shtml. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. David Milgaard Case. 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/david-milgaard-case. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- CBC News. Star Milgaard witness saw visions, inquiry told. 2005. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/star-milgaard-witness-saw-visions-inquiry-told-1.546463. Accessed 05 Feb 2023

- The Globe and Mail. Police didn’t ask about murder, Fisher tells Milgaard inquiry. 2005. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/police-didnt-ask-about-murder-fisher-tells-milgaard-inquiry/article1124015/. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- The Canadian Press. David Milgaard, imprisoned on wrongful conviction, dead at 69. 2022. https://www.cp24.com/news/david-milgaard-imprisoned-on-wrongful-conviction-dead-at-69-1.5904195. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- The Fifth Estate. David Milgaard wrongful murder conviction: Who Killed Gail Miller? (1990) - The Fifth Estate [Internet]. Youtube. 2017 [cited 2023 Feb. 6]; Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aILwMVg_GdY.

- CBC News Online. Indepth: David Milgaard. 2008. https://www.cbc.ca/news2/background/milgaard/. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- True Crime Canada. The Murder of Gail Miller and Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard Part 1 [Internet]. Youtube. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb. 6]; Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t90_UF03Pvk.

- Forensic Science Simplified. A Simplified Guide To DNA Evidence. 2012. https://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/dna/DNA.pdf. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

Join the conversation!

Podcast

Articles

Petitions

Donate

Join Newsletter

Contact Us

Follow us on social media

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Vol. 1, Chapter 3: 36-293.

- Reference re Milgaard (Can.), 1992 CanLII 96 (SCC), [1992] 1 SCR 866, <https://canlii.ca/t/1g2wg>, retrieved on 2023-02-06

- Rossmo, D. K. Dissecting a Criminal Investigation. J Police Crim Psychol. 2021; 36(1):639–651. doi:10.1007/s11896-021-09434-1.

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Public Documents: 217573, 219255.

- The Honourable Mr. Justice Edward P. MacCallum. Commission of the Inquiry Into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. Saskatoon, SK: The Commission; Public Documents: 159853, 229913, 278893-4.

- Stefanidou M, Alevisopoulos G, Spiliopoulou C. Fundamental issues in forensic semen detection. West Indian Med J. 2010;59(3):280-283.

- Innocence Canada. David Milgaard. 2023. https://www.innocencecanada.com/exonerations/david-milgaard/#ftn8. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- SaskToday.ca. Video: Hear David Milgaard's own words on his wrongful conviction. 2022. https://www.sasktoday.ca/north/local-news/video-hear-david-milgaards-own-words-on-his-wrongful-conviction-5621902. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- The StarPhoenix. Commission of Inquiry into the Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard. 2005. https://injusticebusters.org/05Milgaard/Milgaard6.shtml. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. David Milgaard Case. 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/david-milgaard-case. Accessed 05 Feb 2023.

- CBC News. Star Milgaard witness saw visions, inquiry told. 2005. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/star-milgaard-witness-saw-visions-inquiry-told-1.546463. Accessed 05 Feb 2023

- The Globe and Mail. Police didn’t ask about murder, Fisher tells Milgaard inquiry. 2005. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/police-didnt-ask-about-murder-fisher-tells-milgaard-inquiry/article1124015/. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- The Canadian Press. David Milgaard, imprisoned on wrongful conviction, dead at 69. 2022. https://www.cp24.com/news/david-milgaard-imprisoned-on-wrongful-conviction-dead-at-69-1.5904195. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- The Fifth Estate. David Milgaard wrongful murder conviction: Who Killed Gail Miller? (1990) - The Fifth Estate [Internet]. Youtube. 2017 [cited 2023 Feb. 6]; Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aILwMVg_GdY.

- CBC News Online. Indepth: David Milgaard. 2008. https://www.cbc.ca/news2/background/milgaard/. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

- True Crime Canada. The Murder of Gail Miller and Wrongful Conviction of David Milgaard Part 1 [Internet]. Youtube. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb. 6]; Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t90_UF03Pvk.

- Forensic Science Simplified. A Simplified Guide To DNA Evidence. 2012. https://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/dna/DNA.pdf. Accessed 06 Feb 2023.

Comments

Anonymous

March 30, 2023 at 23:05 pm

As a soon to be 30 year old man, I can't imagine what it would have been like living my last 14 years in prison being wrongfully convicted. No money can rewind the clock and bring back all the amazing experiences I've had in my life so far.

SHAre this:

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published

Name

Email

Enter your comment here ...

Post comment

< PREVious article

Next article >

© 2023 Guilty Until Proven Innocent?